Why Does Southern Food Matter?

Southern food matters: it is who we are. Food in the South is distinctly tied to our past, and the soulful creole that telegraphs that past, but also our present and future. All traditions and cuisines began somewhere. Upper Midwest cuisine owes much to Scandinavian immigrants, and Southwestern cuisine is indebted to the aboriginal tribes of the area as well as the Spanish who subsequently settled there. In the South, the traditions did not progress as linearly. Instead they are more accurately likened to a stew, gumbo or pilau: a melting pot, if you will, where the result is greater than the sum of the ingredients. Piedmont cuisine in particular, and Southern foodways are the products of generations of people from disparate backgrounds taking advantage of Mother Earth’s bounty and coming to terms with her capricious nature. The African, Native American, Scots-Irish, German, English Quakers and subsequent peoples who’ve settled in the Piedmont have all transposed something from their culinary traditions onto the ingredients that are indigenous to the climate here and onto those ingredients that were imported and prospered here. Piedmont cuisine is characterized by the dishes that owe their heritage to particular ethnic traditions, such as liver pudding from German immigrants and succotash from Native Americans which are now universally claimed by folks who call the Piedmont home. The dishes have outlasted ethnic divisions. In a recent NY Times article about saving the po-boys of New Orleans, written by Southern food advocate John T. Edge, “Dr. Mizell-Nelson (a historian) believes in the power of public history. He believes that if people know their history, they’re likely to be better stewards of their present.”

“You are what you eat,”cribbed from Brillat-Savarin, is the truth that lies at the center of each person’s identity. To build on the idea that RAFT (Renewing America’s Food Traditions, an organization within Slow Food USA) is promoting, “To save a food that you love, you must eat it,” we can extend this idea to encompass the attitude that in order to preserve our identities and those of our forefathers, we must continue to grow, cook and embrace the foods that they held dear.

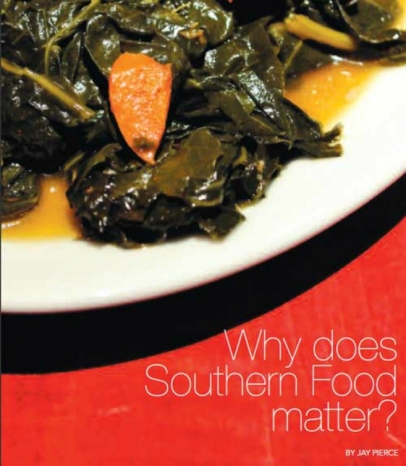

Those comestibles that our ancestors felt distinguished them from others, through necessity or choice, like biscuits, cornbread, pinto beans (with chowchow or onions), cushaw, liver pudding and collard greens, have begun to disappear from our dinner tables and with them, some of our identity.

In this increasingly global village that we find ourselves inhabiting, where sushi can be had in Mocksville, and horchata in Asheboro, who are we, what is our identity and how do we differentiate ourselves from the billions who are not Southerners?We are not content to be a number, part of the faceless masses.We believe in identity and individuality. We believe that our unique pasts make us singularly qualified to make a difference in the world of the future.

What is our anchor?What keeps us rooted in the South and preserves our identity? I believe our common heritage and what defines our “Southern-ness,” is our love of good, down-home, finger-lickin’, roll-upyour-shirtsleeves, lip-smacking, soul-filling food; always with a nod to its origins. We love to eat and whenever we gather around food, the topic of our conversations is inevitably meals past and meals yet to come.

I am a Cajun living in North Carolina – what do I know about Piedmont traditions? I used to be intimidated by North Carolinians, not because of who they are or what they represent, but because I am not one, yet. Still, I endeavor to be successful in recreating their culinary past within the self-imposed constraints of using foods that are locally-sourced, seasonal and grown on sustainable farms.

To steep myself in Piedmont traditions, I reached out to folks whose roots run deep in the region. I spoke to one Greensboro native about her mother’s chicken and dumplings and lemon chess pie, and she brought me samples and the recipes. I asked a grandmother what I should do with persimmons, and she sent me some of her pudding. I set out to perfect Edna Lewis’ chowchow recipe, and I was given several Mason jars of said condiment accompanied by stories of where, and by whom, they were made. I asked around at the farmers’ market about the cushaw squash that I had read about, and someone knew a farmer who was growing what I described, so he called on one of his neighbors to procure some for me. This community embraced me because I demonstrated a genuine interest in the history of the foodways here, and that, by extension, translated to an interest in the identity of the people.

How does my story figure in all of this? Historically, Cajuns have a tendency to be uprooted and transplanted. What we do is adapt to our new surroundings and make them our own. My family is adopting Piedmont traditions as our own, while retaining something of our motherland. My own children don’t know what it means to go to a crawfish boil every Sunday for two months and smell the clouds of cayenne that accompany those events. They do get to enjoy beignets and muffelettas when we go back to visit, but they have no memory of my granny’s chicken and sausage gumbo which we helped ourselves to, as the grown-ups milled around the kitchen on Thanksgiving. Rather, my children’s traditions are of the Piedmont. Their appreciation of barbecue is growing and they associate the month of May with strawberry picking (not the month of February in Ponchatula, like their pop). They’ll eat anything pickled that they’ve been exposed to so far. They understand that apples come from trees, and that beans don’t always need rice if you have chowchow or chopped onions. One way to be of genuine service to our community is by resurrecting the notion of food being intimately connected to its source and reinforcing the seasons’ claim to ingredients like asparagus, strawberries, persimmons and muscadines. If our children expect certain foods to be on the plate because of the time of year, then the markets will respond. We must continue to preach that diversity on the plate as well as in those around the dining room table, will feed our souls. We, as a family and as a community, must see the importance of our forefather’s traditions and perpetuate them so that our children have roots wherever they are planted.

Even AliceWaters realizes the importance of Southern food traditions. Waters, in Greensboro recently for the groundbreaking on the edible schoolyard at the Children’s Museum, pulled me aside and whispered, “Why would your restaurant aspire to be a ‘Meat and Three’?